When you pick up a prescription, you might not think about whether the pill in your hand is the brand name or a generic. But behind that choice is a complex legal and scientific system that determines if the two are truly interchangeable. The FDA therapeutic equivalency codes are the key. They don’t just tell pharmacists which generics can be swapped - they’re written into state laws, shape how much money the healthcare system spends, and decide whether a patient gets the exact same treatment as prescribed.

What the FDA Therapeutic Equivalency Code Really Means

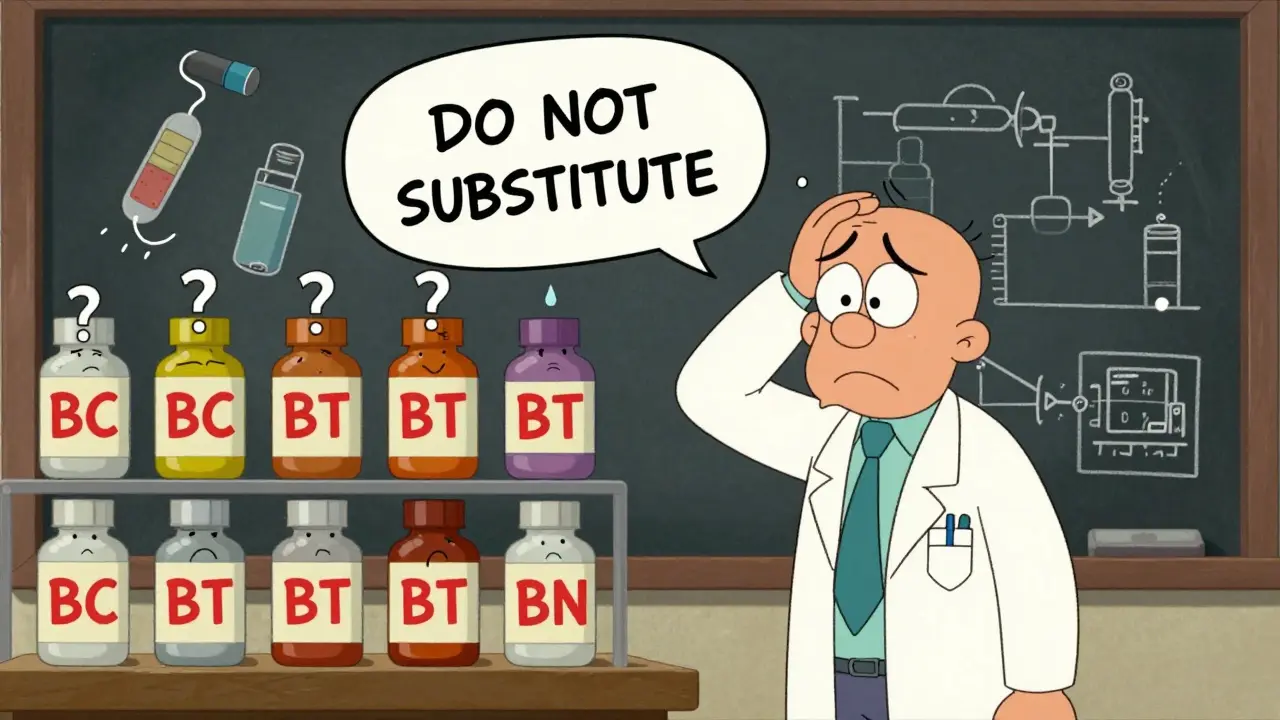

The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs. It also rates them. Every approved multisource prescription drug - meaning any drug made by more than one company - gets a code in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, better known as the Orange Book. This code is two letters: the first tells you if it’s equivalent, the second adds details. An A code means the generic is considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. That’s not a guess. It means the FDA has confirmed the generic has the same active ingredient, same strength, same dosage form, and same route of administration. More importantly, it has proven through real-world testing that it works the same way in the body. The second letter adds nuance: AA means it’s a simple, immediate-release tablet with no issues. AB means it was tricky at first - maybe the formulation was different - but later studies proved it works just as well. On the other side, a B code means the FDA does not consider it interchangeable. This isn’t a judgment on safety. It’s a scientific gap. Maybe the drug is an extended-release capsule, a topical cream, or an inhaler. These are complex delivery systems where small changes in ingredients or manufacturing can affect how the drug is absorbed. The FDA says: we don’t have enough proof yet that this generic behaves exactly like the brand. So, it gets a BC, BT, BN, or another B variant.How the Law Turns Science Into Substitution Rules

The FDA sets the scientific standard. But the law decides what pharmacists can do. All 50 states have laws that allow pharmacists to substitute generic drugs - but only if the FDA says they’re equivalent. That’s it. No state lets pharmacists swap a drug with a B code unless the prescriber specifically says “do not substitute.” California’s law says it outright: substitution is only allowed for products with an A rating. New York, Texas, Florida - they all follow the same rule. The Orange Book isn’t just a reference. It’s the legal bible for pharmacy practice. This isn’t just about paperwork. It’s about real people. If your doctor prescribes a brand-name drug with an AA code, your pharmacist can legally give you the generic. You’ll get the same effect, same side effects, same cost savings. But if your drug has a BT code - say, a topical gel for eczema - the pharmacist can’t swap it unless your doctor writes “dispense as written.” Many pharmacists won’t even try. A 2023 survey found that 68% of pharmacists hesitate to substitute products with B codes, not because they’re unsafe, but because they’re unsure.Why Some Drugs Get B Codes - And Why It Matters

Not all drugs are created equal. A simple tablet is easy to copy. A patch that releases medicine slowly over days? Not so much. Complex delivery systems - like inhalers, injectables, creams, and extended-release capsules - are the main reason for B codes. Take a nasal spray. Even tiny differences in the propellant or particle size can change how much drug reaches your lungs. The FDA has struggled for years to find reliable tests for these products. That’s why, as of October 2023, over 3,400 drugs - nearly a quarter of all listed products - still carry B codes. But the FDA is trying to fix this. In 2023, they launched the Complex Generic Drug Initiative. They’ve cut the average review time for these tricky drugs from 34 months in 2018 to just 22 months in 2023. They’ve also published new draft guidance to help manufacturers prove equivalence for complex products. The goal? Reduce B codes from 24.3% to under 15% by 2027. The stakes are high. In 2022 alone, drugs with A codes saved the U.S. healthcare system $298 billion. That’s 97% of all generic prescriptions. But the $1.7 trillion in total savings since 1995? That’s only possible because patients could swap generics confidently. If B codes stay high, those savings stall.

Who Decides If a Generic Gets an A or B Code?

The process starts with the manufacturer. To get approval, a generic company must file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). They don’t run new clinical trials. Instead, they prove bioequivalence - that their version absorbs into the bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the brand. For simple drugs, this is straightforward. Blood samples are taken over time, and the data is compared. If the curves match within FDA’s strict limits, the drug gets an A code. But for complex products, that’s not enough. The FDA now requires additional testing: in vitro studies, dissolution profiles, even patient outcomes in some cases. If the evidence is solid, the drug gets an AB code - even if it was originally flagged as problematic. That’s what happened with several asthma inhalers and psoriasis creams in recent years. The FDA reclassified them after new data came in. The process isn’t perfect. Brand-name companies often file petitions to block generic approval. In 2022, the FDA received 1,247 such petitions - up 17% from the year before. Many target drugs with complex delivery systems, hoping to delay competition. The FDA reviews each one, but it adds months - sometimes years - to the process.What Pharmacists Actually Do Every Day

For pharmacists, the Orange Book isn’t optional. It’s part of their daily workflow. When a prescription comes in, the pharmacist checks the drug name and strength. Then they look up the TE code. If it’s AA or AB, they can swap it - unless the doctor says no. If it’s BC or BT, they leave it as-is. Many pharmacies now have software that auto-checks the Orange Book and flags non-substitutable drugs. But it’s not always clear. A 2023 survey found that 42% of independent pharmacists struggle with interpreting some B codes, especially for aerosol or topical products. One pharmacist in Ohio told me: “I had a patient come in for a cream labeled BT. I didn’t know if it was safe to swap. I called the doctor. Turned out, the brand was out of stock. We had to wait three days.” That’s the human cost of ambiguity. Even when a drug is approved, the lack of clear guidance can delay care.

What’s Changing - And What’s Next

The FDA is modernizing. In January 2023, they launched a new digital version of the Orange Book with API access. That means electronic health records can now pull TE codes automatically. No more manual lookups. No more outdated printouts. They’re also investing $28.7 million through GDUFA III to develop better science for complex drugs. New testing methods are being tested for inhalers, injectables, and topical products. The goal is to move more B code drugs into the A category. By 2028, experts predict that 93% of all generic prescriptions will be for A-rated drugs. That’s good news for patients and payers. But it also means the FDA must keep pace with new drug technologies - like nanoparticle formulations and smart patches - that challenge the old bioequivalence model. The system isn’t perfect. But it works. It’s saved trillions. It’s kept patients safe. And it’s the reason you can fill a $200 brand-name prescription for $15. All because of two letters: A and B.Why This System Exists - And Why It Matters

The FDA therapeutic equivalency code system didn’t come from a lab. It came from Congress. In 1984, lawmakers passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to fix two problems: high drug prices and long delays for generics. Before this, brand companies could block generics with patents and lawsuits. The law created a path for generics to enter the market - if they proved they were equivalent. The TE code was the solution. It gave pharmacists and regulators a clear, science-based rule. No more guesswork. No more lawsuits over whether a generic “worked.” Just a rating. A legal standard. A savings engine. Today, that system is under pressure - from complex drugs, from industry lobbying, from outdated tools. But its core idea remains: if two drugs are truly equivalent, they should be interchangeable. And if they’re not, we should know why. That’s not just policy. It’s patient care.Can a pharmacist substitute a generic drug without my doctor’s permission?

Yes - but only if the FDA has assigned an 'A' therapeutic equivalency code to that generic. All 50 states require pharmacists to follow the FDA’s Orange Book ratings. If the drug has an 'A' code, the pharmacist can swap it unless your doctor writes 'dispense as written' or 'no substitution.' If it has a 'B' code, substitution is not allowed without explicit permission from the prescriber.

What does an 'AB' code mean on a generic drug label?

An 'AB' code means the generic drug is considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name version, even though it may have had initial bioequivalence concerns. The 'A' means it meets all requirements for substitution. The 'B' indicates it was originally flagged for potential issues - like formulation differences - but later studies proved it works just as well. It’s still safe and interchangeable. Many asthma inhalers and topical creams now carry 'AB' codes after being re-evaluated.

Why do some generic drugs have a 'B' code if they’re FDA-approved?

FDA approval and therapeutic equivalence are two different things. A drug can be approved for safety and effectiveness but still lack enough evidence to prove it behaves exactly like the brand in the body. This often happens with complex products like inhalers, creams, or extended-release capsules. A 'B' code means the FDA says: 'We can’t confirm it’s interchangeable yet.' It doesn’t mean it’s unsafe - just that substitution isn’t legally allowed until more data is available.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The FDA updates the Orange Book monthly. New drug approvals, changes in TE codes, and withdrawals are added each month. As of October 2023, the database included over 14,000 drugs with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. Pharmacists and pharmacies must use the most current version - outdated print copies are no longer legally acceptable for substitution decisions.

Do over-the-counter (OTC) drugs have therapeutic equivalency codes?

No. The FDA’s therapeutic equivalency coding system applies only to prescription drugs approved under Section 505 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. OTC medications - like pain relievers or antacids - are not evaluated or coded in the Orange Book. Substitution of OTC drugs is handled by retailers and consumer choice, not federal law.

Can a generic drug have a different TE code than another generic of the same brand?

Yes. TE codes are assigned to each specific product - not to the drug in general. Two different generics of the same brand-name drug can have different codes if their formulations differ. For example, one generic might be an immediate-release tablet (AA), while another is an extended-release capsule (BC). Even if both contain the same active ingredient, the delivery system changes the equivalence rating. Always check the exact product name and TE code, not just the drug name.

laura Drever

January 13, 2026 AT 02:32the orange book is a joke. half these bc codes make no sense. i saw a bc topical cream yesterday and the brand was discontinued. pharmacist just shrugged. patients suffer because bureaucrats cant decide if a cream is the same.

Clay .Haeber

January 14, 2026 AT 20:51oh wow. so the fda spends millions to tell us what we already know: complex drugs are complex. genius. next they’ll publish a 300-page white paper on why water is wet. also, who gave these people the right to decide if my eczema cream is ‘interchangeable’? i didn’t vote for this.

Priyanka Kumari

January 15, 2026 AT 00:58as someone from india where generics are the only option for most, i’m amazed at how much care the us system puts into this. yes, it’s slow. yes, it’s bureaucratic. but at least there’s a system trying to protect patients. in my country, we get generics with no testing at all. this orange book? it’s a lifeline.

Jesse Ibarra

January 15, 2026 AT 14:54let’s be real - this entire system is just a fancy way for big pharma to delay generics under the guise of ‘science.’ they fund ‘studies’ that ‘prove’ equivalence isn’t possible, then sit back while prices stay high. the ‘b code’ is a corporate loophole dressed in lab coats. the fda’s ‘initiative’? a public relations stunt. they’ve known this for 20 years.

and don’t get me started on the 1,247 petitions. that’s not science - that’s legal terrorism. every time a generic maker tries to bring down a price, the brand company throws a tantrum in court. the system isn’t broken. it’s rigged.

and yet you’ll hear people praise this as ‘patient safety.’ what a joke. patient safety is paying $15 instead of $200. patient safety is not waiting three days for a cream because some pharmacist is too scared to read the damn code.

Milla Masliy

January 16, 2026 AT 16:59my grandma takes three different creams for her arthritis. two are aa, one is bt. she has no idea what any of it means. the pharmacist just hands her the bottle and says ‘this one’s different.’ she trusts them. but if she had to choose? she’d pick the cheapest. the system should be simple. not a maze of letters only pharmacists understand.

why not just label it: ‘swap allowed’ or ‘ask your doctor’? no jargon. no orange book lookup. just clarity. patients aren’t scientists. they’re people trying to get better.

lucy cooke

January 17, 2026 AT 17:24the real tragedy isn’t the b codes - it’s that we’ve turned healthcare into a bureaucratic poetry slam. we have 14,000 drugs, each with a two-letter code that determines whether someone gets relief or waits. and we call this ‘progress.’

we could’ve built a system where all generics are presumed interchangeable unless proven otherwise. instead, we built a castle of doubt. every ‘b’ is a whisper of fear. every ‘a’ is a victory over profit. and still, we argue over particle size like it’s a divine secret.

the future isn’t in more testing. it’s in trust. trust that science can be simple. trust that patients can be trusted. trust that $298 billion in savings isn’t just a number - it’s lives.

Alan Lin

January 18, 2026 AT 12:48as a pharmacist with 18 years of experience, i can tell you: the orange book is the only thing standing between chaos and consistency. yes, the b codes are frustrating. yes, some are outdated. but if we remove this framework, we open the door to liability, error, and harm.

i’ve had patients come in furious because their ‘same’ cream changed texture. they thought it was a different drug. it wasn’t - it was a different generic with a different excipient. the te code warned us. without it? we’d be guessing. and guessing kills.

the solution isn’t to abandon the system. it’s to fund better science, update the software, and train pharmacists better. the code isn’t the problem. the underfunding is.

sam abas

January 20, 2026 AT 10:42funny how the article says ‘the system works’ but ignores that 42% of pharmacists struggle with b codes. if the system works, why are half the people using it confused? also, ‘the orange book is the legal bible’? that’s not a compliment - that’s a cry for help. we’re running a multi-billion dollar health system on a printed pamphlet from 1984.

and why does every comment about ‘complex delivery systems’ sound like someone reading a phd thesis? if a cream can’t be swapped because of ‘particle size,’ then we need better tech, not more bureaucracy. fix the science. don’t just label it b and call it a day.

James Castner

January 22, 2026 AT 07:51we are witnessing a quiet revolution in pharmaceutical equity - one encoded in two letters, yet carrying the weight of millions of daily decisions. the therapeutic equivalency system is not merely regulatory; it is a moral architecture. it forces us to confront the tension between innovation and accessibility, between precision and pragmatism, between corporate interest and public health.

the ‘b’ code is not a failure - it is a humility marker. it says: we do not yet know enough. and in a world that demands instant answers, that restraint is noble. yet we must not mistake restraint for stagnation. the 22-month review time is progress - but it is not enough.

we must invest not only in bioequivalence testing, but in public literacy. patients deserve to understand why their cream is labeled ‘bt’ - not because they are stupid, but because the system has failed to translate science into meaning. the orange book must become a living document, accessible, understandable, and integrated into every digital health record - not buried in a PDF only pharmacists dare to open.

the $298 billion saved is not a statistic. it is the difference between a child with asthma breathing freely and gasping for air. between a veteran with psoriasis sleeping through the night and lying awake in pain. between dignity and desperation.

the two letters - a and b - are not just codes. they are the punctuation of justice.

vishnu priyanka

January 23, 2026 AT 16:55bro, the real flex? the fda lets you swap a $200 pill for $15 and calls it ‘science.’ meanwhile, my cousin in delhi pays $2 for the same pill and no one checks if it’s ‘equivalent.’ we don’t need a code - we need more of these generics to exist everywhere.