When your world suddenly spins out of control - like you’re on a merry-go-round that won’t stop - and your ear feels stuffed with cotton, your hearing muffled, and a ringing noise won’t go away, it’s not just dizziness. It could be Meniere’s disease, a hidden disorder rooted deep in your inner ear. This isn’t something you can shake off with rest. It’s a chronic condition driven by fluid buildup, immune chaos, and structural changes you can’t see. And it’s more common than most people realize: about 1 in 2,000 people live with it, mostly between ages 40 and 60.

What’s Really Going On Inside Your Ear?

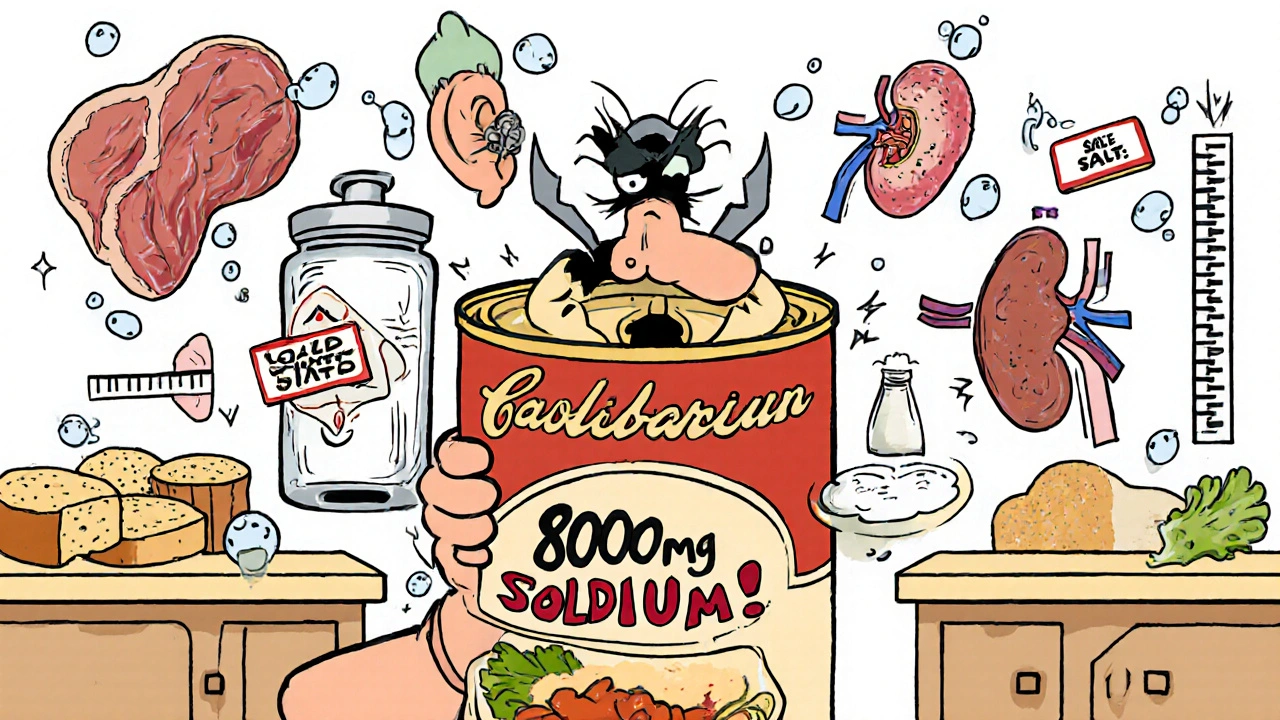

Your inner ear isn’t just a hearing organ. It’s a complex hydraulic system. Two fluids flow through it: one is potassium-rich endolymph, the other sodium-rich perilymph. They work like batteries - their balance lets your brain understand movement and sound. In Meniere’s disease, too much endolymph builds up. This is called endolymphatic hydrops. It’s not just extra fluid; it’s pressure. And that pressure stretches and damages delicate membranes. Recent 3D imaging studies show that the saccule (a tiny sac in the inner ear) swells in 97% of cases, while the utricle (another balance organ) only bulges in about a third. Why? Because its membrane is thicker - 12.5 micrometers on average - compared to the saccule’s 8.2 micrometers. Thinner walls stretch easier. When these membranes stretch too far, they rupture or leak. That’s when vertigo hits. The brain gets mixed signals: your eyes say you’re still, but your inner ear screams you’re spinning. And it’s not just mechanical. Your immune system is involved too. Studies show immune cells in the inner ear pump out inflammatory chemicals like IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IL-17 - up to five times higher than in healthy people. These chemicals break down the blood-labyrinth barrier, letting immune cells swarm in. Over time, this causes scarring in the endolymphatic sac - the organ meant to drain excess fluid. When that sac gets clogged or fibrotic, fluid can’t escape. The cycle keeps going.Why Salt Matters More Than You Think

You’ve probably heard to cut back on salt if you have Meniere’s. But why? Because your inner ear works like your kidneys. The stria vascularis - a tissue in the cochlea - produces endolymph the same way kidney cells make urine. Too much sodium in your blood? Your inner ear follows suit. More sodium pulls more water into the endolymph space. That’s why doctors recommend keeping sodium intake under 2,000 mg a day - ideally 1,500 mg. A Stanford University study found that low-sodium diets reduce endolymph production by 23% to 37%. That’s not a small win. For many, it cuts vertigo attacks in half. It’s not about avoiding salt shakers alone. Processed foods - canned soups, bread, deli meats, sauces - are the real culprits. One serving of canned soup can hit 800 mg. That’s over 40% of your daily limit before breakfast. Track your intake. Use apps like MyFitnessPal. Cook at home. Rinse canned beans. Choose fresh over packaged. It’s tedious, but it works. In fact, 55% to 60% of patients see improvement with diet alone. Combine it with a diuretic like hydrochlorothiazide, and that number jumps to 70%.Medications That Actually Help

Not everyone responds to diet and diuretics. For those who don’t, doctors turn to targeted treatments. Intratympanic corticosteroid injections - steroid shots delivered directly into the middle ear - work in 68% to 75% of cases. The steroid doesn’t just calm inflammation; it helps regulate sodium and water transport in the inner ear. A 2025 study showed it reduces endolymph volume by 31% to 44% in responsive patients. The procedure is quick, done in a clinic, and has minimal side effects. For severe, disabling vertigo that doesn’t respond to steroids, intratympanic gentamicin is an option. This antibiotic kills off the balance sensors in the inner ear. It sounds extreme - and it is. But for people who can’t work or drive because of constant spinning, it’s life-changing. It controls vertigo in 85% to 92% of cases. The trade-off? Up to 18% risk of further hearing loss. It’s a calculated risk: trade some hearing for stability. Newer drugs are on the horizon. A 2025 clinical trial tested an anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody - a drug originally developed for psoriasis - in Meniere’s patients. Results? Vertigo attacks dropped by 63%, and hearing loss slowed by 41%. These aren’t cure-alls, but they’re the first treatments that target the immune root, not just the symptoms.

Surgery: When All Else Fails

Surgery is never the first step. But for the 25% of patients who don’t improve with anything else, options exist. Endolymphatic sac decompression - opening up the sac to improve drainage - helps with vertigo in 60% to 70% of cases. But it rarely improves hearing. Why? Because by the time surgery is considered, the hair cells in the cochlea are often already dead. No amount of drainage can bring them back. A more aggressive option is vestibular nerve section - cutting the nerve that sends balance signals to the brain. It stops vertigo almost completely (95% success), preserves hearing, and requires hospitalization. It’s reserved for patients with good hearing who still can’t function. The least common - and most extreme - is labyrinthectomy, removing the entire inner ear on the affected side. It ends vertigo and hearing on that side, but it’s only done when the ear is already deaf and the vertigo is unbearable.What Happens Over Time?

Meniere’s isn’t static. It changes. In the early stages, you get sudden, violent vertigo attacks - lasting 20 minutes to several hours - followed by periods of calm. Hearing fluctuates. Tinnitus comes and goes. But after 5 to 10 years, something shifts. The inner ear becomes so swollen with fluid that the membranes stop rupturing. The spinning stops. Sounds good, right? Not quite. Now you’re stuck with constant unsteadiness - like walking on a boat. Your hearing is permanently damaged. Studies show 72% of long-term patients lose more than 50 decibels of hearing in the affected ear. That’s like trying to hear someone speaking from across a noisy room. And here’s the twist: 18% of cases never involve hearing loss at all. These are called vestibular Meniere’s. They’re often misdiagnosed as regular vertigo. But they respond better to vestibular rehab - balance training exercises - than traditional Meniere’s.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a specialist to start helping yourself.- Start a low-sodium diet now. Aim for under 1,500 mg per day. Cut out processed foods.

- Keep a symptom diary. Note when attacks happen, what you ate, stress levels, sleep. Patterns emerge.

- Try vestibular rehab. A physical therapist can teach you exercises to retrain your brain to rely less on your inner ear.

- Reduce stress. It doesn’t cause Meniere’s, but it triggers attacks. Meditation, walking, yoga - they help.

- Avoid caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine. They affect blood flow to the inner ear.

Why This Isn’t Just ‘Bad Luck’

For years, Meniere’s was called a mystery. Doctors shrugged. But science is catching up. It’s not one thing. It’s a mix: fluid drainage problems, immune overreaction, genetic risks (12% of familial cases link to SLC26A4 gene mutations), and even past viral infections. That’s why one-size-fits-all treatments fail. The future is personalized. Imagine a scan showing exactly where your endolymph is building up. A blood test revealing your immune markers. A treatment plan built for your body - not a general guideline. That’s already happening in research centers. In five years, we may have blood tests to predict who’ll develop Meniere’s before symptoms start. Right now, the best thing you can do is act. Don’t wait for the next attack. Start with your diet. Track your symptoms. Talk to your doctor. Meniere’s isn’t curable - yet. But it’s manageable. And with the right approach, you can still live well.Can Meniere’s disease go away on its own?

Meniere’s disease doesn’t typically go away on its own. While vertigo attacks may lessen over time - especially after 10 to 15 years - the underlying fluid imbalance and hearing damage usually persist. What changes is the pattern: the violent spinning stops, but constant unsteadiness and permanent hearing loss often remain. Early management can slow progression, but spontaneous full recovery is extremely rare.

Is Meniere’s disease the same as vertigo?

No. Vertigo is a symptom - a spinning sensation - that can come from many causes like inner ear infections, BPPV, or migraines. Meniere’s disease is a specific disorder that causes vertigo along with hearing loss, tinnitus, and ear pressure. Not all vertigo is Meniere’s, but Meniere’s always includes vertigo.

Do diuretics really help with Meniere’s?

Yes, for many people. Diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide reduce fluid buildup in the inner ear by helping the kidneys remove excess sodium and water. Studies show they reduce vertigo attacks in 55% to 60% of patients, especially when combined with a low-sodium diet. But not everyone responds - about 40% see little or no benefit, often due to structural issues in the endolymphatic sac.

Can stress trigger Meniere’s attacks?

Stress doesn’t cause Meniere’s, but it’s a well-documented trigger for attacks. High stress raises cortisol and adrenaline, which affect blood flow to the inner ear and can worsen fluid pressure. Many patients report attacks following major life events - job loss, illness, or emotional trauma. Managing stress through sleep, exercise, or therapy can reduce attack frequency.

Will I lose my hearing completely?

Not necessarily - but it’s a real risk. About 72% of people with long-term Meniere’s lose more than half their hearing in the affected ear. Hearing loss usually starts low-frequency and worsens over time. Early treatment - especially with steroids and diet - can slow or even prevent this. Once hair cells in the cochlea die, they don’t regenerate. That’s why acting early matters.

Are there new treatments on the horizon?

Yes. The most promising are immune-targeting drugs like anti-IL-17 antibodies, which reduced vertigo by 63% in recent trials. Researchers are also exploring gene therapies for those with inherited mutations and advanced imaging to detect fluid buildup before symptoms start. While not yet widely available, these treatments could shift Meniere’s from symptom control to disease modification within the next decade.

John Kang

November 26, 2025 AT 16:25Been living with this for 8 years and the low-salt thing actually works if you stick to it

Not saying it’s easy but cutting out canned soup and deli meat cut my attacks in half

My doctor said I was crazy at first but now he’s the one pushing it to everyone

Bob Stewart

November 28, 2025 AT 10:57The pathophysiology described is accurate: endolymphatic hydrops results in mechanical distortion of the Reissner membrane and subsequent disruption of ionic homeostasis

Immune mediators including IL-6 and TNF-alpha contribute to fibrosis of the endolymphatic sac

However, the claim that 55-60% of patients improve with diet alone lacks robust longitudinal data and may reflect selection bias in clinical cohorts

Simran Mishra

November 29, 2025 AT 13:12I know this sounds crazy but I started drinking warm lemon water every morning and my vertigo got better

I used to cry every time I stood up and now I can walk to the mailbox without feeling like I’m gonna fall

I don’t know if it’s the lemon or the water or just finally giving myself a moment to breathe

But I’ve been doing it for six months and I swear it’s changed everything

People think you’re just being dramatic when you say your world spins

But they don’t feel it

They don’t know what it’s like to be trapped inside your own body

And I just want someone to say I’m not imagining it

Even if it’s just this one comment

Thank you for writing this

Holly Lowe

November 29, 2025 AT 22:27Y’all need to stop treating this like a death sentence

Meniere’s ain’t the end of your life it’s just a new level in the game

I went from barely leaving the house to hiking mountains last summer

Low salt? Check. Vestibular rehab? Double check. Stress? I meditate like it’s my job

Yeah I got tinnitus now but I don’t let it run my life

You don’t have to be a victim

You can be the boss of your own inner ear

Orion Rentals

November 30, 2025 AT 03:18The data regarding intratympanic gentamicin is compelling with success rates exceeding 85% in refractory cases

However, the risk of permanent sensorineural hearing loss must be weighed against functional impairment

Current guidelines recommend this intervention only after failure of conservative management and in patients with significant vestibular dysfunction

Sondra Johnson

December 1, 2025 AT 14:23Someone mentioned the anti-IL-17 trial and I’m crying happy tears

Finally someone’s treating this like an autoimmune disorder and not just ‘bad luck’

I’ve been told for years it’s all in my head

Now science is saying no - your immune system is literally attacking your ear

And if that drug works even half as well as they say

I’m gonna start a support group just to scream about it

Chelsey Gonzales

December 2, 2025 AT 14:58low salt = no more attacks? i thought it was just a myth

but i tried it and holy crap i havent had a spin in 3 months

also i stopped drinking coffee and i dont even miss it

its wild how much your body listens when you stop being mean to it

MaKayla Ryan

December 3, 2025 AT 21:16Why are we wasting time on diets and injections when we could just fix the system?

Stop eating processed garbage and get off your couch

Every single person I know with this disease is either overweight or addicted to sugar

It’s not magic, it’s basic biology

Stop looking for pills and start looking in the mirror

Kelly Yanke Deltener

December 5, 2025 AT 04:23I read this whole thing and I just felt so seen

My husband thinks I’m dramatic when I say I can’t get out of bed

But he doesn’t know what it’s like to lose your balance in the grocery store

Or how your hearing just… fades like a bad radio signal

Thank you for writing this

I’m not broken

I’m just fighting a war no one else can see

And I’m not giving up